How Cultural Assets Are Being Sold Off in the Name of Expansion

Article prepared by Save the National Glass Centres campaigner Jo Howell. Have you noticed this trend from UK Universities? Let us know in the comments.

Across the UK, universities have evolved into powerful economic entities, not just centers of education but also significant players in the property market. With rising financial pressures and the need to secure alternative income streams, many universities have increasingly turned to land development and real estate ventures. However, this trend is not without consequences, particularly for arts and cultural organisations that risk being displaced or sold off to make way for commercial ventures.

One of the most poignant examples of this growing tension between university growth and cultural preservation is Sunderland University, where the development of property has raised alarms about the potential loss of cultural landmarks—particularly those that have long been vital to the upward social mobility of local working-class communities.

Universities as Land Developers: A New Financial Reality

In recent years, universities across the UK have sought to capitalise on the booming property market. With government funding cuts, higher tuition fees, and the increasing cost of running educational institutions, many universities have turned to real estate development as a lucrative means to generate additional revenue. Property projects, ranging from student accommodation to commercial spaces and research hubs, have become key parts of university expansion plans.

While these developments are often marketed as essential for the growth of the university itself—allowing for better facilities and more student spaces—the consequences for local communities, particularly arts and cultural organisations, are more complex. The land acquired for development is often situated in city centers or areas that are home to arts organisations that are vulnerable due to limited funding.

This trend has raised concerns that universities, once stewards of local culture, are now prioritising commercial interests at the expense of cultural spaces. In some cities, the push for university-driven property development has led to the closure or relocation of long-standing cultural venues—spaces that have traditionally provided a platform for creativity, community expression, and social engagement.

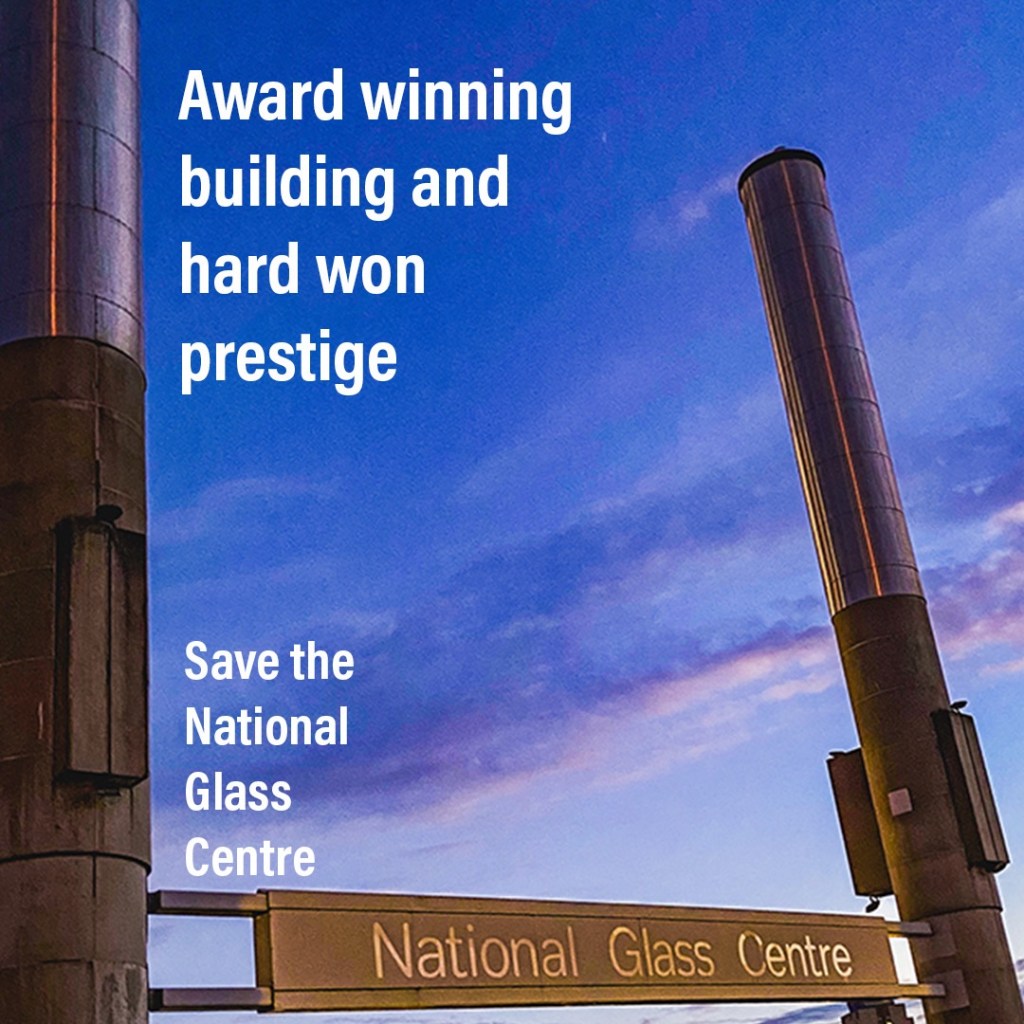

The National Glass Centre: A Cultural Anchor for Sunderland’s Working-Class Communities

In Sunderland, the issue has come into sharp focus with the case of the National Glass Centre (NGC), a cultural institution that holds immense significance for the local community, particularly working-class families. The centre, established in 1998, has not only been a hub for the arts but also a key vehicle for upward social mobility and aspirations in a city that has long struggled with economic hardship and social inequality.

For generations, Sunderland has been known for its industrial heritage, with shipbuilding, coal mining, and glass manufacturing at the heart of its economy. However, as these industries declined, the city faced significant social challenges, including high unemployment and limited opportunities for young people. In this context, the NGC became more than just a museum or gallery. It represented hope and possibility for many working-class individuals who had limited access to cultural or educational opportunities. The centre provides workshops, apprenticeships, and hands-on training in glassmaking—skills that have empowered local people to enter creative and technical fields.

The NGC is a place where many young people, often from disadvantaged backgrounds, are introduced to new possibilities that extend far beyond their everyday experiences. For these individuals, the NGC has been a critical part of building self-esteem, confidence, and career aspirations. It represents the kind of cultural resource that challenges traditional class boundaries and fosters a sense of belonging in a city that has long been overlooked.

However, as Sunderland University has expanded its footprint in the city, the NGC has faced increasing pressure. In recent years, the university has made moves to develop the surrounding land, raising fears that the NGC will be displaced in the name of progress. Local arts advocates worry that if this trend continues, the NGC may eventually cease to exist. Thus losing its community-focused identity, likely to be replaced by private development or luxury student accommodation.

The High Cost of University Expansion

The growing tendency for universities to act as developers has led to a broader debate about the role of these institutions in shaping the physical and cultural landscape of cities. While it’s undeniable that universities play a crucial role in regional economic development, their increasing focus on property development has often come at the cost of cultural assets that are integral to the local identity.

The National Glass Centre’s role in promoting upward social mobility highlights a crucial aspect of this debate: cultural institutions are not just places for artistic expression but vital vehicles for social change. They provide the working-class population with opportunities that would otherwise be inaccessible, offering not only educational benefits but also fostering community cohesion and pride.

For many in Sunderland, the loss of such cultural institutions would represent more than just the demolition of buildings; it would signify the loss of a unique cultural heritage that has allowed local people to dream beyond the limitations imposed by their circumstances. The National Glass Centre, in particular, provides a rare example of an arts institution directly contributing to the aspirations of its community for a better life, offering skills and opportunities that many other parts of the country currently envy.

The Balance Between Growth and Culture

The growing involvement of universities in property development raises an important question: How can institutions balance their ambitions for growth with their responsibility to protect and nurture the cultural assets that are integral to their local communities?

University executives are key decision-makers in this process and must consider not just the financial viability of their ventures but also the broader social impact of their decisions.

University-driven redevelopment should not come at the cost of the community’s cultural wealth.

A Call for Thoughtful Development

The case of the National Glass Centre in Sunderland serves as a poignant reminder of the importance of cultural spaces in creating pride and providing opportunities for young people. Moving forward, it is essential for universities to reconsider their approach to development strategies. Ensuring that the benefits of growth are shared equally with the arts and local communities, not just the commercial entities that stand to profit from redevelopment.

The challenge for universities is to find ways to grow without losing sight of their role as stewards of culture and community. It is possible to foster educational and financial growth while also safeguarding the cultural heritage that enriches local life. The time has come for universities to develop a more balanced approach—one that acknowledges that true progress cannot be measured in property alone but in the social and cultural impact they leave behind.